Nothing Beside Remains: A History of the New Weird

0. A New Tradition

There’s a line in an old Martin Petto review of Zachary Jernigan’s No Return that prompted me to take a long hard look at my understanding of the recent history of genre literature. Having explained that Jernigan’s book is not actually about the brutal face-punching depicted on its cover, Petto observes that Jernigan uses so many tropes from so many different genres that attempting to locate these tropes within a particular literary tradition is effectively impossible:

This unrestrained playfulness is on display in another notable feature of the book: its treatment of speculative fiction tropes. Jernigan exuberantly picks and chooses what he wants without paying any attention to the box it has come out of. It is not simply that any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic—the descriptions themselves are now interchangeable. Berun was explicitly made by a wizard but he might as well be a robot and the language used to describe him even hints at nanotechnology.

This observation immediately transported me back to 2004 when I reviewed China Miéville’s Iron Council and specifically praised him not only for his use of SFnal techniques in a Fantasy novel, but also the threat this type of genre bending posed to what I then saw as traditional Fantasy writing:

Magical ideas are discussed in the way we might discuss scientific ideas, these are not mysterious forces but simple facts about the world that can be exploited by anyone with the right kind of knowledge. Bas Laag might seem alien to us but never to Miéville's characters. It is Miéville's creativity and his approach to genre conventions that has lead many to hail him as the saviour of fantasy. I think that he is something quite different; China Miéville is the most dangerous man in fantasy. By showing real creativity and placing the onus upon the Other rather than the familiar Miéville is showing us quite how flawed and abusive our relationship with fantasy really is. If Miéville's style becomes as influential as it doubtless deserves to be then the safe familiarity of much of fantasy writing is seriously under threat.

A lot can change in the space of thirteen years. Back when Miéville first began attracting attention, his indifference to traditional boundaries seemed not just refreshing but downright heroic. Here was a commercial Fantasy writer who used techniques more closely associated with Science Fiction and Horror and managed to attract a huge readership and mainstream attention in the process. Miéville’s success not only challenged conventional thinking about what audiences expected from genre literature, it also hinted at a brave new world in which genre writers might be freed from their commercial shackles and allowed to explore fresh forms and new ideas. In 2004, China Miéville was not just an interesting young writer, he was a herald of the apocalypse... an apocalypse that had been a long time coming.

Over a decade later and it feels as though we have always been at war with genre boundaries. The language of boundary-defiance has now been internalised to the point where genre culture has begun to lose touch with the historical and economic contexts that made the creation of those boundaries seem like a good idea at the time. Far from remaining an approach favoured by outsiders and radical innovators, genre bending is now seen as a somewhat problematic dominant paradigm. Expectations that once helped guide readers to their preferred styles of book are now little more than glass-jawed phantoms, easy to defeat and easy to define oneself against. However, traditions are easiest to deconstruct when they are not your own, the genre culture that Miéville railed against is not the genre culture of today and so there is little that is either heroic or noteworthy in a contemporary writer blurring genre boundaries. As Petto puts it:

Steph Swainston was perhaps too far ahead of the curve when she published The Year of Our War in 2004; now it seems all the best new writers take this hybridity for granted. Quietly, without any fuss, the New Weird has won.

Petto is correct when he says that today’s writers relate to genre boundaries in a different way than those of previous generations, but the far more interesting and contentious claim is that the New Weird played a pivotal role in bringing that change about. Curious about whether this claim stood up to anything even approaching close scrutiny, I set out to examine the history of the New Weird. What I found was both an answer to the question of whether or not the New Weird had ‘won’ and a number of insights into how the field renews itself over time. This is an account of the lifecycle of the New Weird… how it was born and reborn first as politics, then as commerce and finally as a symbol that was as inspirational as it was frustrating.

1. First as Politics

2003 was a watershed year in the history of science fiction.

Inside genre, a cohort of talented British writers were making waves and generating the kind of creative energy that would result, two years later, in an all-British Hugo shortlist referred to in the November 2003 issue of Science Fiction Studies as the ‘British Boom’.

Outside genre circles, the unprecedented popularity of British YA series such as Harry Potter and His Dark Materials was (somewhat perversely) putting pressure on the idea that genre literature was only of interest to children. Faced with what appeared to be a genuine cultural phenomenon, the British media latched onto a photogenic Marxist graduate student named China Miéville and made him the face of contemporary genre writing.

Often, when writers who work in commercial genres gain a degree of mainstream acceptance, they begin to feel pressure to distance themselves from their genre roots and stress the fact that they are ‘not like other girls.’ This allows mainstream literary institutions to maintain the illusion of meritocratic open-mindedness whilst also damning the majority of genre writers with faint praise: Of course there are always going to be a few rough diamonds producing serious work for genre imprints but they really are the exception that makes the rule as most genre writing is about tedious elves, super-intelligent squid and shirtless tycoons!

To his eternal credit, China Miéville not only refused any and all attempts at re-branding, he went out of his way to stress the vibrancy of the genre culture that surrounded him. Miéville’s refusal to deny his roots put mainstream cultural journalism in something of an awkward position as his unapologetic attitude meant that they couldn’t cover Miéville without also covering the rest of genre.

Though most of Miéville’s contemporaries were aware that British SF was in rare form, the sudden explosion of mainstream media interest seemed to come as something of a surprise. Aside from providing opportunities for genre writers to publicise their work to a wider audience, this interest also served to open up a variety of new cultural spaces where people could encounter and discuss genre literature without having to muddy their boots in fandom. Interviews with mainstream journalists and appearances at mainstream literary festivals promised not only better PR and different audiences but also a chance to write a different kind of fiction, one that was unconstrained by the demands and expectations of traditional genre publishing. Terrified that this opportunity to write new things for new audiences might be snatched away, people like Miéville, Jon Courtenay Grimwood, Justina Robson, Gwyneth Jones and Muriel Gray appeared in a number of unexpected places (such as London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts) to bang a drum for the vibrancy of contemporary genre literature.

1.1 The TTA Press Forums Discussion

NB: The original TTA Press forums are no longer online but the entire discussion was captured, saved and made available on the website of Kathryn Cramer. Thanks to Will Ellwood for making me aware of their continued existence.

When popular cultural history tells us that the New Weird was born of lengthy discussions held on the now defunct TTA Press forums in May of 2003, it is tempting to imagine a well-ordered discussion in which a bunch of people hammered out a shared set of sensibilities, identified literary pre-cursors and set a creative agenda that would allow them to promote themselves as a new movement. This is not what happened in the sprawling 100,000-word discussion that took place between April 29 and July 23 2003. In fact, many of the loudest voices in the discussion went out of their way to prevent just this sort of ‘productive’ outcome. One of the major strands of the discussion involved whether or not the group should even bother to name itself. As the anthologist Jonathan Strahan put it:

I think it's a load of old cobblers. Much like the new space opera (a term invented by a bunch of critics to cover the fact that they got distracted by cyberpunk and didn't notice that no-one had stopped writing the other stuff), the new weird/new wave fabulist/slipstream whatever seems to be a pretty happy and healthy outgrowth of some things that came before which would probably be much better off if left unlabelled and left to grow in the dark where they belong. I certainly can't believe that you (MJH), China, VanderMeer, or anyone else would be better off if you were packaged up with some handy-dandy label.

Names are problematic things in literature as anything that can be named can be turned into an anthology and anything that can be turned into an anthology can be misunderstood, misrepresented and drained of all creative potential. In so far as the history of science fiction is shaped by polemical anthologies, that history is a procession of tombstones erected where vibrant cultural moments once took place. However, as much as the authors in the discussion were reticent to assume the shape of a movement, there was also a belief that if they did not name themselves, someone would come along and do it for them. As M. John Harrison explained:

If I don't throw my hat in the ring, write a preface, do a guest editorial here, write a review in the Guardian there, then I'm leaving it to Michael Moorcock or David Hartwell to describe what I (and the British authors I admire) write. Or, god forbid, I wake up one morning and find *you* describing me. There's a war on here, Jonathan. It's the struggle to name. The struggle to name is the struggle to own. Surely you're not naive enough to think that your bracingly commonsensical, "I think it's a lot of old cobblers" view is anything more than a shot in it?

Someone named Henry captured the logic involved in naming something that has yet to acquire any defining characteristics:

I reckon that it's more useful to think of the New Weird as an argument. An argument between a bunch of writers who read each other, who sometimes influence each other, sometimes struggle against that influence. Who don't ever agree on what the New Weird is, on where it starts and stops, but are prepared to harangue each other about it. Describing the New Weird in these terms involves its own kind of codswallop, but at least it's a less constricting kind of codswallop.

Far from being a label applied to an existing sub-genre or sensibility, the term ‘New Weird’ was adopted in an effort to buy some time and allow the people involved to decide what, if anything, they were going to do with their new cultural spaces and the unique cultural moment that had created them. The author Paul McAuley captured the mood with a quote:

Came across this quote by David Bowie, from a late ‘70’s Charles Shaar Murray Interview. It is about how punk rock was killed off by too many bands diving into the category instead of striving to be assessed outside it; I think that it sums up the problem of *any* new genre trying to maintain its identity: “…None of them are saying *we are us*. They’re saying *yeah, we are punk* and in so doing they’re putting a boundary on their writing scope, which is a shame because there could be a real movement of sorts. But you have to let a movement remain as a subculture for a little while and gain some — I’m wary of using the word ‘maturity’ — gain some recognition of its own relationship with the environment it lives in.” There’s a warning. Fly under the radar until you are ready to Shock and Awe.

This quote is useful in helping us to understand the chaotic nature of the discussion as well as the reticence to channel the discussion’s energy into such traditionally ‘productive’ avenues as adopting literary ancestors or drawing up manifestos. Many people seemed to believe that the combination of a particularly vibrant British scene and an abundance of mainstream interest had served to create a unique opportunity to change not only the shape of the genre but also the shape of British literary culture as a whole. Most of the people involved in the New Weird discussions recognised this revolutionary potential but many seemed reluctant to do anything to steer or shape this potential lest their meddling break the spell, collapse the wave function and waste the opportunity to see that revolutionary potential reach its full magnitude.

This fear of breaking the spell is so tangible that much of the discussion came to revolve around identifying potential threats to the cultural moment. Justina Robson identified one particular external threat when she raised the issue of mainstream authors moving into the new cultural spaces:

This is a war, the winners get all the loot and to name the Truth. I think MJH is right. It's also why his stand to claim the right to define, and China's stand, and my stand (see ICA May 14) is pissing in the wind unfortunately as none of us has Recognised Power of Naming. I think that Literature is going to come to SF and try and take the entire thing over by main force in the next 5 years.

This may seem histrionic but consider the types of books that turned up on the Arthur C. Clarke Award shortlists throughout the ‘00s, the rise of Young Adult fiction, and the simple fact that many cutting-edge works of British science fiction are now being published either by smaller genre imprints or by publishers working outside of the genre and Robson’s words begin to seem prescient.

As a self-described veteran of “two or three” literary revolutions, M. John Harrison described the internal difficulties of sustaining a moment of cultural change:

Carpetbagging: once the New Wave parameters were codified, there was a general softening-off as second generation writers stripped out the edgier stuff. I mean, I think it's inevitable that people seeking to understand a movement select the similarities rather than the differences between exponents. That drives you towards the mean--the main stream. New writers imitate that, & before you know it, the energy's gone, because it lay in the creative tensions between the different exponents.

Dangers both internal and mainstream were identified quite early on but much of the heat in the discussion came from the fear that genre culture would take the revolutionary potential of the New Weird and New Space Opera moments and use it to create nothing more adventurous than a tepidly-received anthology with a single print run. This apocalyptic spectre first surfaced in the form of the New Wave Fabulist anthology Conjunctions: 39 edited by Bradley Morrow and Peter Straub (a tepidly-received anthology with a single print run).

Having contributed to the anthology and been called a New Wave Fabulist by Jonathan Strahan, M. John Harrison explains:

I believe I'm an honorary New Wave Fabulist, yes, along with about twenty other puzzled people. Generous of Brad Morrow to bestow that laurel on me after I so repeatedly savaged his New Gothic in the TLS in the 90s.

Harrison’s attitude towards the inauthenticity of Conjunctions: 39 is important not only because some contributors tried very hard to attach the New Weird to New Wave Fabulism, but also because New Wave Fabulism is a perfect example of what it was that the people participating in the discussion were attempting to avoid: The New Weird lacked a movement but had a moment filled with potential for cultural change. New Wave Fabulism had an anthology and a set of submission guidelines but no apparent connection to an identifiable cultural moment. What potential New Wave Fabulism might once have had evaporated the second its principles were codified in the form of an anthology. As Paul McAuley would later put it:

Submission Guidelines for New Wave Fabulist Fiction? Christ. How quickly the bottomfeeders spot a Trend.

Alastair Reynolds also voices concern that defining the New Weird might wind-up restricting its development:

You're only ever successful on your own merits, not if you live according to a formula. That's what worries me about establishing a 'new' genre in too defined a way; the work becomes formulaic, you create the mean that MJH describes above, and that's what people start to write to. More broadly, when someone like China - or in fact when a group of writers like the various folk referenced above - appear with a bang, I think that creates another problem. China (I assume) writes from his involvement with Marxism / Max Ernst / Mervyn Peake / whatever else - MJH, you've talked about Katherine Mansfield / HE Bates / post structuralism etc above - Justina, I'm sure you have similarly wide roots. But the risk is that people will come along and not immediately see the roots, and just go 'I want to write like China / MJH / Justina / whoever' - rehashing not newly creating.

This fear that the energy of the moment might somehow be diffused or re-directed by the process of codification was so intense that people even seemed reluctant to discuss the possibility that the New Weird might have been distinct from the Radical Hard SF and New Space Opera moments that were associated with the sudden and unexpected explosion of talent in British genre writing. M. John Harrison again:

I'm aware here that I'm not talking directly about the New Weird, & that I've bundled it with Brit SF. Deliberately, because I see them both as responses--or not quite that, probably some better word--to the same situation, which is the increasing convergence of concerns between literary mainstream fiction and f/sf.

While the obvious fragility of the cultural moment may have inspired some participants in the debate to treat the New Weird like a wounded fledgling, others were a good deal more bullish about the opportunity it represented. Despite now being seen as one of the founding figures of the New Weird, Jeff VanderMeer was immediately sceptical about the utility of applying labels to his writing:

Sticking these examples into the same file folder marked "Surreal Cityscape Subgenre" doesn't do that much good as far as I can see. I kind of like "New Weird" because it acknowledges the pulp influences in the work, but it's still amorphous and inaccurate. Now I'm going to go back to writing my novel. It doesn't particularly care what it's called as long as when I finish it it doesn't have five arms and no legs.

VanderMeer then followed this up with a battery of questions that revealed all of the (more of less hidden) assumptions that had been at work in the discussion up to that point; Was the New Weird just a British thing? Was there really a conflict between genre and mainstream? Was the New Weird inherently political? Was the New Weird anything other than a sycophantic cult of a successful author and media darling? The reactions to VanderMeer’s questions are fascinating as while many commentators attempt to provide answers, M. John Harrison treated VanderMeer’s contribution as an attempt to force a new agenda on the discussion:

I’m not going to answer all your amazingly crisp points because if I did I would be accepting that agenda, & I don’t. (…)Part of your crisp, beautifully presented agenda is designed to question that, perhaps redefine the phenomenon to include US fiction which I would think of as a different type. That’s one of the reasons I introduced, early on in this discussion, the idea of defending one’s own definition of things. That’s why naming is owning. You & I are aware of that. Aren’t we, Jeff?

This initial skirmish between those who wanted the discussion to serve some sort of practical purpose and those who wanted to see where the discussion might wind up of its own accord sets the tone for much of the 100,000 words that followed. The New Weird discussions are a fascinating critical document; a chaotic warren of more-or-less comprehensible conversation fragments on issues ranging from the nature of truth to the purpose of literature, the realities of genre publishing and whether or not British genre culture is distinct from American genre culture. However, as timely and thought-provoking as these discussions may be, they are dominated by tensions between the potential and the practical. In fact, the whole discussion can be seen as a series of attempts to impose a practical agenda on an otherwise open-ended conversation. Mindful of the growing tension between authenticity and anything approaching a useful purpose to the discussion, China Miéville’s first contribution attempted to challenge the idea that any form of practical constraint would instantly kill the New Weird:

I'm not particularly advocating a manifesto or a sign-up sheet or anything. But I'm saying that thinking consciously in terms of a specific grouping or movement is potentially at least as enabling as it is constraining. Every time we accept a commission to write for a themed anthology we are acknowledging that constraints can be enabling - a movement or a manifesto is merely an exaggeration of that.

He continued:

Whether or not we agree that New Weird is a useful grouping, the dissing of it on the basis that it is a 'label' is too limited. Of course that still leaves open the question of whether it is useful, but that's another argument - many of those who argue against it in the threads elide the two points, they argue both against 'labels', and then against the putative specifics of the New Weird. As an aside, I'm astonished by the number of claims that this label (or all labels) is no more than 'a marketing gimmick'. Undoubtedly, if this caught on, marketers would attempt to use it - just as they do, ad nauseam, with 'surrealist'. However, this doesn't mean that 'surrealist' isn't a useful term, only that those of us who care about what it fucking means have to have the argument with severity on an ongoing basis. Me, I think New Weird is currently a useful category, a useful argument, so I'll use it.

Well received, this post did silence some of the more pessimistic voices in the discussion. However, while the idea that the New Weird should just be allowed to do its thing without any artificial intervention was quietly shelved, the debate simply moved on from ‘Codification is death’ to ‘This Particular Form of Codification is Death’. For example, the writer Richard K. Morgan appears under the name Richard and proclaims his deeply relaxed attitude towards the market forces unleashed by commodification:

Think of the way writers like Salman Rushdie paved the way for the huge swathe of what I suppose you could call the British post-colonial culture novel. These days the blurb of every third book you pick up in Waterstones begins "Rashid lives with his eccentric old aunt in a run down suburb of Bombay/Kingston/Nairobi and dreams of...." Some of this stuff is good, some of it's awful, but the main thing is it's taken seriously. The same could also be said for the "Dreadful life experience during convulsive social upheaval in China" novel. I guess there's no good reason for the New Weird not to go the same way. The giants of the genre can go on surfing their wave for as long as it lasts, and the secondary practitioners then nip in behind on lesser swells. Different surfers drop out when the size of the wave ceases to suit their particular temperament/stomach for the stuff. None of that's *bad* as such. In the end, writers want to make a living (I know I do), and that's far easier to do within the context of a swelling, powerful genre, rather than chipping away in a desert, unappreciated.

Little more than a reminder that publishing is and always has been a business, this contribution attracted a forceful rejection from M. John Harrison:

That's a view which plays well with editors and agents. But it seems like a complete capitulation for a writer. I watched the New Wave carpetbagged in the same way, and I'm still disgusted. I *don't* forgive all those nice, flaccid, mediocre people who diluted and rediluted something strong & worthwhile, just because, well, they had to make a living. They could have stayed with their day job as far as I'm concerned, because they *didn't contribute*. […] The idea that this process "can't" be changed also plays well with editors, especially corporate editors, because it ensures no one will ever try.

To which Morgan responded:

This is the old Gatekeeper scam - We know what's good, and if You disagree it's because You don't have the levels of sophistication (which We of course do) to engage correctly with the material. In short, We are better than You. Yeah, *right*. Look, all I'm doing is looking for a bit of general tolerance here - taste is a very variable thing, and you've got to be very careful indeed before you start saying things like *my taste is superior to yours* - because that way Margaret Atwood lies.

Rejecting Morgan’s tolerance of populism out of hand, M. John Harrison formulated a response that exposed many of the group dynamics and psychological forces at work in the discussion:

Two more points. (a) I feel that the arguments you put forward are a limit, on me, personally. I feel that they are designed to stop me from thinking what I think, and writing what I write: not just in books, or in newspapers and magazines, but here on my own message board. I feel your presence here as a brake. I feel it as the old fashioned Science Fiction Superego, whose job is to bring me down and bring me to earth. Not just me, perhaps, but all writers who want to... well, just do what they want. I don't *want* that, Richard. I don't *want* what you want. I resent it. I've had it stuffed down my throat for nearly forty years. It's the boring old received wisdom of the genre, and I don't really see why I should have to put up with it again, especially here, and in the middle of a discussion that *did* interest me. (b) By defining a type of writing, you have defined an audience. You are content to keep writing into that audience. Your publisher is *very* content for you to keep writing into that audience. Some of us would like to make inroads into a new audience. In this thread we were discussing how we might do that, how we might go forward into the new century and entertain new people and learn new things, and generally have some thrills and spills on a real learning curve. You seem to have come here as a censor, to herd us back into a field whose existence as a pure entity we question--though we respect much of the fiction it has produced in the past. The world is a big old place Richard. Tell you what. You stay home, that's fine. But it's just a bit village-elder of you to try keep everyone else there too.

In this response we see not only the fear of being sucked back down into gears of commercial genre publishing but also a very raw and personal fear of losing one’s personal and literary identity in the rush towards group mobilisation and commercialisation. It is interesting to note that while M. John Harrison discusses a lot of things in these threads, he is never more forceful or articulate than when he is trying to protect what he sees as an opportunity to do something legitimately new.

A more successful attempt to impose some practical order on discussions came in the form of a long post by the academic Farah Mendlesohn who attempted to tie the New Weird to what she calls ‘Liminal Fantasy’, one of the four main forms of fantastical literature identified in Mendlesohn’s 2008 book Rhetorics of Fantasy. Mendlesohn not only identified literary ancestors (Harrison’s Viriconium and Peake’s Gormenghast) and limited discussions to the fantastical, she also suggested connections to New Wave Fabulism and the attempt to:

Write the ordinary as if it is fantastical, and allow the fantastical (rather than the fantasy, which is slightly different) to remain latent. (…) We see something as fantastical and so do the characters, but they don’t see it as fantastical in the same way. (…) Our sensibility as to what is mimetically real is being screwed with. (…) That dissonance between what we think is fantastical and what the characters do seems pretty crucial to me.

The idea is that while we (the readers) might see magic and dragons as unreal and fantastical, characters in a fantasy novel will see them as nothing more than spectacular elements of the real world. The dissonance that Mendlesohn was gesturing towards would produce a literature that accepted the complicated and artificial nature of our concept of the ‘Real World’. As M. John Harrison put it:

The best works in Conjunctions seem to me to have something new in f/sf. Sophisticated technique, liquid boundaries and high levels of humanity enable statements that are at once pure fantasy and outright metaphor. Even in the New Weird those two modes are supposed to be mutually exclusive. Some of those stories are so precariously balanced that precariousness becomes a strength in itself. You don’t know which way they’re going to fall — mainstream or fantasy. Then you push them, you find you *can’t* make them fall. They’re held rigid (& you with them) in this exquisite paradox, fantasy/not-fantasy.

Sensing that the conversation may have shifted for good, Al Reynolds expressed his concern about the unexpected amputation of SF from the New Weird:

If it were indeed seen as a defining characteristic of the New Weird, I’d have to define myself as not writing it. MJH was kind enough to mention my name early on in the first New Weird thread, but for me it’s *vital* to give that sense of connection back to the real world.

Worried that this sudden outbreak of productivity might have taken them too far from the rich potential of the cultural moment, there followed an undignified attempt to find some shared ground between Mendlesohn’s attempt at making the New Weird a ‘fantasy thing’ and the desire to keep people like Alastair Reynolds inside the tent. Filing the whole thing under the thematic rubric of ‘Frame-of-reference’ problems, Steph Swainston explained:

I was left with a simple recognition that the real world is so mind-bogglingly weird, so rich with detail, so full of trials that our best toolbox has to be observation and a distilling of our own experiences into fantasy - and a good dash of the science news into SF. MJH mentions this above when he says: “the notion that you can perhaps write fantasy without any (or at least much) fantasy in it.”

This idea that SF is part of the New Weird because SF is ultimately nothing more than fantasy with “a good dash of the science news” is important both for what came later and for understanding Swainston’s perspective on what was going on. One of the first posts in the discussion is Swainston’s attempt at a literary manifesto and it is striking in so far as it perfectly captures what we now think of as the New Weird:

The New Weird is a wonderful development in literary fantasy fiction. I would have called it Bright Fantasy, because it is vivid and because it is clever. The New Weird is a kickback against jaded heroic fantasy which has been the only staple for far too long. Instead of stemming from Tolkein, it is influenced by Gormenghast and Viriconium. It is incredibly eclectic, and takes ideas from any source. It borrows from American Indian and Far Eastern mythology rather than European or Norse traditions, but the main influence is modern culture — street culture — mixing with ancient mythologies. The text isn’t experimental, but the creatures are. It is amazingly empathic. What is it like to be a clone? Or to walk on your hundred quirky legs? The New Weird attempts to explain. It acknowledges other literary traditions, for example Angela Carter’s mainstream fiction, or classics like Melville. Films are a source of inspiration because action is vital. The elves were first up against the wall when the revolution came, and instead we want the vastness of the science fiction film universe on the page. There is a lot of genre-mixing going on, thank god. (Jon Courtney Grimwood mixes futuristic sf and crime novels). The New Weird grabs everything, and so genre-mixing is part of it, but not the leading role. The New Weird is secular, and very politically informed. Questions of morality are posed. Even the politics, though, is secondary to this sub-genre’s most important theme: detail. The details are jewel-bright, hallucinatory, carefully described. Today’s Tolkeinesque fantasy is lazy and broad-brush. Today’s Michael Marshall thrillers rely lazily on brand names. The New Weird attempts to place the reader in a world they do not expect, a world that surprises them — the reader stares around and sees a vivid world through the detail. These details — clothing, behaviour, scales and teeth — are what makes New Weird worlds so much like ours, as recognisable and as well-described. It is visual, and every scene is packed with baroque detail. Nouveau-goths use neon and tinsel as well as black clothes. The New Weird is more multi-spectral than gothic. But one garuda does not make a revolution… There are not many New Weird writers because it is so difficult to do. Where is the rest? Jeff Noon? Samuel R. Delany? Do we have to wait for parodies of Bas-Lag? MJH how many revolutions have you been part of?? The New Weird is energetic. Vivacity, vitality, detail; that’s what it’s about. Trappings of Space Opera or Fantasy may be irrelevant when the Light is turned on.

The eviction of SF from the cultural moment continued with the arrival of the American anthologist Kathryn Cramer who was keen to roll the New Weird up in the same carpet as the New Wave Fabulists and make both movements about the deconstruction of traditional genre boundaries:

One question I had been thinking about was how to distinguish what we're calling here the New Weird from plain old slipstream. In addition to the New Weird's emphasis on fantasy and horror over sf, the other primary distinction seems to me to be the approach to genre boundaries. Both slipstream and the New Weird are notable for their engagement with subverting genre boundaries. However, where the slipstream approach to genre has been for the writer to position the work slightly outside the conventional boundaries of the genre, so that it might be taken for a work of Postmodern Literature, writers of the New Weird seem (at least in part) to lack the drive to break out and be lifted up to mainstream recognition. Rather, writers of the New Weird enjoy playing with genre boundaries for their own sake, because they are a good toy.

This prompted the first of what would be many withering replies from M. John Harrison:

I don't think I would be interested in a game. You would have to count me out if it was that. I'm fairly certain it isn't one, but if for the purposes of discussion you defined it as that, then I wouldn't be interested in the discussion that ensued. Games are for people who aren't willing to take risks. You play tennis with stuff, you might as well play tennis.

Cramer then unpacked her remarks and explained that her talk of games was a way of talking about genre in more sociological terms. M. John Harrison seemed to accept this but remained unconvinced by the idea of fiction that sets out to engage with genre expectations:

I see only a kind of maximum writing space, in which every technique from every genre is available to solve the individual problem of the individual writer on the day. (That is, you have something to say: how do you set about saying it ?) That crosses not only subgeneric boundaries, but the great boundaries too, between biography and fiction, or fiction and journalism. Even to say "cross" or "boundaries" is to buy a set of artificial limitations. There's only write-space, in which you make your choices according to how difficult a problem you have and how clever you are at combining modes and techniques. Boundaries only exist to be negotiated because of corporate land grabs and academic enclosures, which are constantly presented to the writer as manifest, proper, and--most definite of all--fixed. (…) When you tell me about the delight of "games" played between categories, you are serving the land-grab agendas which gave rise to literary academicism and corporate publishing. You're effectively offering, out of the goodness of your heart, to rent back some of the common land. I don't want that, thanks. I want to do what I want. In fact, actually, I already do. The New Weird is a small move by some writers to site themselves more fully in write-space; elsewhere, on the "mainstream" side of one of those illusory fences, authors like David Mitchell are making similar kinds of moves. The word these days is pick & mix. It is take what you need. Do the job right and you won't need to apologise, in fact do the job right *and people won't even notice* that you broke these nonexistent rules and bred H P Lovecraft onto Joanna Trollope using a little Alpine journalism to lubricate the sex act itself. Inasmuch as it's an expression, in its own way, of that mood among writers, the New Weird is worth a go. But not as a game, because that game can only be played by rules someone else put in place.

Still perplexed and seeking common ground, Cramer attempted to unpack her understanding of genre as well as her role as a professional in genre publishing:

A genre is the set of codes defining a transaction between reader and text. A marketing category is a set of codes defining a transaction between a publisher and a distribution system. These interact through the book's package: a book should be packaged honestly enough so that it does not outrage the consumer (the reader who bought it based on the package), and at the same time it must look like something the industry is accustomed to selling. These cues also come into play in reviewing, since the publishers cue the reviewers as to the nature of the book. (…)On renting back the common lands: Sure I make a certain amount of money off the sweat of the brows of writers. (Our household economy is founded on that!) Regarding me in particular, one could make arguments one direction or another regarding hard sf. I do a kind of activist anthology which does serve both corporate and academic agendas by providing a neat little package that says HARD SF on the cover making things very easy. However we are also very consciously revising and documenting the genre codes both for readers and for writers. I don't think the common lands formulation is a good fit. From my perspective, marketing categories are confining and genres are liberating.

Provoked by Cramer’s attempt to transform the New Weird into something more concrete, Justina Robson laid out her attitude to genre boundaries:

One of the things I found hardest to cope with at Clarion, and since at other out and out SF gatherings, is the sense that people have a huge amount invested in keeping up walls between genres, particularly in their case SF and anything else. This came from both sides; editorial/corporate and writer/fan. Because the writers are at the sharp end of this (and actually the fans, although they don't want to know about it much) there was a big fear about writing anything a bit different. The same thing is going on here as in the movie industry, although its taking a slightly different road. But the thing that drives all this conformity to accepted norms is the servicing of the free market and largely American illusions about economic growth and stability, visions underpinned by a view of the world which is convinced that sufficient marketing analysis will eventually yield a perfect solution to the problem of how to shift product and what product will shift most. Because writing isn't just about selling units, it's also about selling ideas, the restriction on the structures and categories through which ideas can be questioned is acting as heavy leverage on publishing's massive hedge fund. Literally and metaphorically. Continuing to accept genre norms as anything except temporally convenient markers for discussing a social phenomenon is like accepting the idea that scientific advances, free market capitalism, democracy and the modernisation of the world will eventually bring an end to human conflict.

To which M. John Harrison added:

We don't live in a world of rigidly-definable states anymore. Compartmentalising metaphors don't catch the motion of things--complexity theory describes the world as a dynamic tangle of boundary-conditions, phase changes and abrupt, unpredictable jumps between attractors: a fiercely agitated place of emergent properties, combination and recombination, indescribably complex activity resulting from the application of simple rules: not a little Swiss town with well-demarcated sectors, or an apothecary-chest divided into lots of tiny little boxes. Readers who can manage Light or The Scar or Falling Out of Cars as easily as a Mitchell or Murakami novel--or for that matter, literary editors who find themselves able to read Light as easily as they read Everything Is Illuminated or The Corrections--seem to me to be the proof that a reading-space now exists which owes little or nothing either to academic constructs like genre or marketing constructs like... genre. I'm interested in defining, helping to construct, then taking writerly advantage of that space.

The conflict between Cramer and the New Weird is reminiscent of the Third Man argument from Plato’s Parmenides: Cramer viewed genre as a set of protocols which, though social, are part of the real world. Sensing that authors were growing dissatisfied with those protocols, Cramer proposed the creation of an additional set of protocols that, despite being rooted in Fantasy, allow for carefully choreographed and pre-negotiated use of non-Fantastical protocols. The New Weird responded to this by explaining that Cramer had completely misunderstood the entire point of the discussion: They were not looking to build another genre box, they wanted to destroy all existing genre boxes and produce work in a space that owed nothing to the people who benefited from existing genre infrastructure. Finally (after some inspired mockery by Cheryl Morgan) the penny dropped and Cramer asked:

Do I gather here that this amorphous thing that we must not call a genre is not intended to be the next big thing, promoting some writers and excluding others, but rather is intended as a set of liberatory tools available to all, if only they will use them?

A struggle to understand the emancipatory purposes of the New Weird project is also evident in the consternation of Jeff VanderMeer who distanced himself from the New Weird label out of a desire to attain the kind of expectation-free writing spaces that the New Weird seemed devoted to creating:

I don't think New Weird encompasses what I want to write in general. For one thing, I have this idea that I don't ever want to write the same book twice. This of necessity means that even if I wrote a "New Weird" book (and I think the last 100 pages of Veniss Underground definitely qualify as well as some of City of Saints, but not all), I would soon be out of the New Weird subset anyway. Do labels like this attach themselves to the skin or to the bone marrow? Do the original cyberpunks still feel constrained by that label? Probably not, but I can't speak for them. So perhaps there's no harm in it. And yet I see a lot of indications that "fantasy" is entering the mainstream and transforming it, so I'm also wary of possibly limiting myself by throwing in my lot with the New Weirds (assuming the New Weirds want me. lol!). Am I reading you right, Cheryl? That a New Weird book has to have a certain political orientation? Because that's a deal breaker for me. I'm left of center, but confining myself to a particular political viewpoint in my fiction seems...dull.

The growing divide between British people who ‘got’ the New Weird and American people who were terribly excited despite not being clear about what was going on prompted Paul McAuley to suggest there might be a real cultural difference in how British and American people apprehend the nature of genre:

There seems to be a cognitive dissonance on either side of the Atlantic between how categories break out or arise. Over in the States, there seems to be an anxiety about taxonomy and ancestry that I think we're mostly trying to avoid over here, contrary badge-refusing Brits that we are. What's clear to me is that, because we are a smaller system over here, we need less thermal input to fluidise our boundaries and create all kinds of the exciting eddies.

Turning to contemporary politics for inspiration, McAuley attempted to explain that the ambiguous and chaotic nature of the New Weird was a deliberate feature rather than a bug that needed ironing out:

A long way back in this thread, MJH mentioned a point I raised at the ICA event, which was that as a nascent (lower-case) movement, the NW lacked a focus or obvious public platform. His riposte was that as a post-Seattle phenomenon, it didn't need one. It generates its own momentum wherever it can in an unstructured, horizontal non-hierarchical fashion - which is, when you think about it, the ideal kind of SF movement for those of us who don't like SF that reinforces the status quo. Its usefulness, I think, lies in the unsettling power of something which isn't yet pinned down in any way, like a pawn about to make the move to line 8 on the board, and transform into whatever's most useful for the game at that moment.

Confused as to what ‘post-Seattle’ might mean, Cramer resorted to semantics in an effort to impose her vision of the New Weird:

One could try to argue that it is a mode rather than a genre (an argument that works well with horror which crops up disconnected from any marketing of genre connections) except that those of us who are discussing have strong genre connections.

The discussion ignored this suggestion and set about drilling down into how the New Weird perceived genre and what M. John Harrison referred to as “writing space”. Returning to the conversation for the first time in a while, Jonathan Strahan summarised the fruits of the discussion up to that point:

There is a change at the deeper levels of, for want of a better term “writing space” or “story space” where things are melding and changing. One of the expressions of that is what you see in the New Weird, another is in the New Space Opera. I suspect, though, if we were to look closely at the continuing evolution of fiction generally, that such changes are showing up all over the place. It’s only that we are more likely to notice them in our own backyard. I’d also add that what seems valuable to me about this conversation, running across six weeks, three continents, a range of topics, and including a diverse range of writers, critics and just plain interested folk is that it is the step BEFORE the recognition of a Movement or a sub-genre or whatever. It predates the manifesto, the list of writers and the selection of core texts. Rather, it’s the discussion that allows thoughts to be gathered, ideas to be tested, etc. I can’t imagine how it would have happened before the net — it certainly would have been much slower, if it was possible at all — and I think it’s particularly valuable given what seems to be the possibility of a real divergence in the traditions of US/UK genre fiction.

Having failed to convince anyone that the New Weird should be viewed not as the end of genre expectations but as the beginning of a new mode, Cramer attempted to manacle the New Weird to the Fantasy genre. She did this by trying to funnel all discussion of current trends in Science Fiction to her own personal website and out of the New Weird discussion entirely:

However, is seems to me that there is a larger renegotiation of the nature of genre going on that is under discussion here using the special case of the New Weird but in which space opera and hard sf keep cropping up. I don't want to take the air out of the larger discussion.

It is not clear how you might go about discussing “a larger renegotiation of the nature of genre” without mentioning Science Fiction but Cramer’s calls for a new thread went unheard and prompted both a detailed response from Al Reynolds about the importance of weirdness to contemporary SF and a spectacular piece of passive-aggression from M. John Harrison:

I think that's fine, Kathryn. Nice of you to give us a license for continued operation.

Frustrated by the discussion’s refusal to follow her agenda, Cramer began to grumble about the New Weird’s inability to issue a members list and suggested that the movement’s intransigence might well have lost them not only an important ally but also the opportunity to be marketed as something important:

This is an interesting and energetic conversation. But a discussion of genre boundaries needs to encompass more writers, works, and publications than can be accommodated in a discussion of the New Weird. Defined by process of elimination, the New Weird is rapidly shrinking. Remaining New Weird writers are, by my count, MJH, China, Justina, maybe Gabe, and one or two drafted posthumously. Everyone else has been shot down or left. Al Reynolds is irretrievably New Space Opera unless he can be wooed away from accommodating reader expectations. We should pay very close attention to Jeff VanderMeer's departure (taking with him the crowd he publishes, I think), Jeff having concluded that he will not be using the term New Weird. With Jeff's departure, a significant majority of writers negotiating a new relationship with genre are out. As I stated (in my June 4th post), there is a widespread change in writers' relationships to genre boundaries that is different than Slipstream. I am now convinced that this is not the New Weird, but something else which is perhaps in need of naming.

This toothless threat to pick up someone else’s ball and go home if they won’t play properly prompted a forceful response from China Miéville:

Um. At the risk of sounding shirty... "[A] discussion of genre boundaries" may "need" to encompass more writers, etc, as suggested but so what? That's not what's going on here, at least that's not what I'm doing. And I BANG AND BANG AND BANG my head against a wall at the thought that the New Weird can be "defined by process of elimination". It precisely *can't* be defined that way. We're back to sodding positivist bean-counting. New Weird - like most literary categories - is a moment, a suggestion, a tease, an intervention, an attitude, above all an argument. You cannot read off a checklist and say 'x is in, y is out' and think you've understand what's at stake or what's being argued. See Al's own reaction to 'NW' stuff, refusing to say 'well I do space opera so I'm "out"'. Things can be both in and out, some writers may think they're in but be out, others may despise the idea but be in, *this is as it should be*. And when the notion stops being interesting or useful - either because it *wins the argument* in some currently inconceivable way, or because it loses by being transmogrified into a checklist like this, then we should stop talking about it.

Drained of energy after months of continuous debate, the discussion slowly began to wind down leading Justina Robson to draw the literary side of the New Weird debate to a close:

I think that we've realised that there are 2 things going on in this discussion - one is the writing of realism-bending fiction and one is the philosophical enquiry about the nature of inner reality and its projection into the outside world. For the writing side, I think we've said all we can say. On the philosophical side I think there's a long way to go.

Having worked my way through these discussions, I remain convinced that something important was reflected by the TTA Press forums in the spring of 2003. However, contrary to popular belief, these discussions were not the birthplace of a new movement or sub-genre.

What these discussions contain is something far more primal and basic than the emergence of a genre; what they reflect is the troubled birth of a new literary subjectivity… One so raw and unformed that it was not ready to yield the sort of practical outcomes demanded by the wider genre community or the commercial interests attached to it. If we must talk about the New Weird being born of the discussions that took place on the TTA Press forums then let us speak only of it having been a still birth. The thing we now refer to as the New Weird is an entirely different creature, one stitched together from the skin and entrails of a subjectivity that was never allowed the time or the space in which to fully become itself.

1.2 Without Subjectivity, There Can Be No Movement

Every cultural entity (be it a genre, a sub-genre, a scene, a movement, or a school) is born of a particular place and time… a sudden awareness that the wider culture has changed and that the old tools are no longer up to the job. Given time, a shared response to a shared cultural moment can yield new techniques, new forms, new arguments, and new styles of collective action but before any of these productive outcomes can take place, people need to realise that they are not alone. They need to look around at the other people beside them and say “Is it just me or did you feel that too?”

The moment in which creative people realise that they are not alone is the moment in which a new collective subjectivity is born, and this is precisely what the TTA Press discussions contain. The reason the discussions seem unproductive and aimless is that most of the people involved in the discussion were still trying to work out what they felt and whether what they felt resembled what anyone else felt. People who bounced out of the discussion like Richard Morgan and Jeff VanderMeer bounced because they were not a part of that subjectivity… they saw the world in different ways and were not part of that particular cultural moment. They were not there when it happened, whatever ‘it’ may have been.

I think of this stage in the lifecycle of the New Weird as ‘politics’ because the creation of new subjectivities is the wellspring of all political action. Every great political movement is born of the twin realisations that we are not alone and that something must be done. However, what (if anything) does eventually get done is determined not only by the nature of the change that created the new subjectivity in the first place but also by the character of the people involved in the birth. Given that the New Weird moment happened to a group of writers working within British SFF in the early years of the 21st Century, it was perhaps inevitable that the New Weird moment should eventually yield essays, anthologies and publishing lines but the New Weird was never allowed to become its own subjectivity. People were too quick to demand results and too eager to impose their own pre-existing ideas on what should have been an organic prise de conscience. Impatient and grasping, genre culture wrenched the New Weird from its original subjectivity and released it onto the Internet to fend for itself. Half-born and not yet weaned, the New Weird would spend the best part of a decade being maligned and misconstrued by a culture less interested in new subjectivities than in product that is both marketable and digestible.

2. Then as Commerce

Seeing as the New Weird was allowed neither the time nor the space in which to define itself, it should come as no surprise that the term ‘New Weird’ entered the cultural bloodstream without a clear definition. Looking through the search results for the term ‘New Weird’, it is striking both how quickly the term entered common use and how little effort was made to explain what it actually meant. Consider, for example, this interview with the literary agent John Jarrold from 2004:

China Miéville and the New Weird will bring a number of new authors into fantasy where swords and dragons are not the norm, which has to be healthy for the genre.

Equally puzzling is Ross E. Lockhart’s 2006 suggestion that the New Weird marked the genre’s return to its pulpy roots and a period when genre expectations had not yet been codified:

Until only recently, with the appearance of the genre-bending urban noir fantastic of the New Weird, the literary realms of pre-historic swordsmen’s adventures and modern-era detective stories were regarded by most readers as topics miles apart from one another.

So the New Weird is both a new form of epic fantasy and an attempt to wind back the clock to an era of more fluid genre conventions? Early critics seemed just as confused.

2.1 A Buzzword

One of the first attempts to map the new critical territory was an essay by Shaun C. Green that appeared in December 2003. Entitled “The Uncanny in China Miéville’s “New Weird”: An Examination of Perdido Street Station and The Scar”, Green’s essay associates the New Weird with Miéville’s preoccupation with what some literary theorists refer to as ‘the uncanny’:

This developing area of fantastic literature can be related to ideas discussed in Bennett and Royle’s essay — specifically, to quote, “with how the ‘literary’ and the ‘real’ can seem to merge into one another” [17] when considering the uncanny. As Bennett and Royle observe, uncanniness could be considered to be when ‘real’ life takes on a ‘literary’ quality or, on the other hand, the ‘literary’ is the type of writing that most consistently invokes and engages with feelings of uncanniness. The “New Weird”, as earlier discussed, is a reflection of an inherently political (and social, and cultural, and personal) reality, but one which is intertwined with fantastic elements. Here is a most overt juxtaposition of the real and the fantastic; the uncanniness of Miéville’s New Weird fiction can thus be considered to derive from either the elements of the fantastic that infiltrate the real, or from the way that the alien contains so many disturbingly familiar elements that we recognise as real.

Drawing upon both the TTA Press discussions and an interview with Miéville that appeared in a 2002 issue of the British Science Fiction Association’s critical journal Vector, this essay presents the New Weird as a form of Fantasy literature that distinguishes itself by a more complex and ‘political’ attitude towards both our reality and that of the text. In other words, Green identifies the New Weird as an example of what Farah Mendlesohn calls Liminal Fantasy. It is interesting to note that Green downplays the genre-bending aspects of the New Weird:

This term is conceived as a response to a number of factors affecting and affected by the literature of the fantastic, including but not limited to the increasing breakdown of genre boundaries. The “New Weird” is not intended to be a new category to replace the old, but rather demarcates a time when some things are changing and new things are happening within a field of literature.

This characterisation differs markedly from that of the academic Roger Luckhurst whose 2005 book Science Fiction presents the New Weird not only as an explicitly Science Fictional movement but also one that was born of the 1990s rather than the 2000s:

What is striking about SF in the 1990s is that it responds to the intensification and global extension of technological modernity not with new forms, but rather with ones lifted from the genre’s venerable past. The New Space Opera or the New Weird, coinages for trends within 1990s SF, revive modes from the 1920s and 1930s.

Having identified the New Weird as a 1990s phenomenon for the sake of his book’s internal chronology, Luckhurst proceeds to conflate the New Weird with New Wave Fabulism, suggests that Miéville’s Marxist politics are central to the ‘dark fantasy’ aspects of the New Weird and concludes with a quote from John Clute that emphasises not only the fantastical nature of Miéville’s writing but also his sustained critique of traditional genre boundaries:

It is only with the new century that what one might call genre-morphing has become a central defining enterprise within fantastic literature

The confused and contradictory nature of Luckhurst’s assessment of the New Weird is not only a product of an academic culture that rewards people who publish first rather than people who publish accurately, but also a clear indication that contemporary critics did not know what to make of the New Weird as a concept.

Despite the authors of the New Weird making it clear that they were wedded to a particular cultural moment and that the nature of this moment made ideological statements both impractical and inadvisable, critics completely ignored the wider context of the original discussions and set about trying to construct a movement out of the few fixed points they had: The works of China Miéville, the words of M. John Harrison and a list of authors who mostly didn’t identify as New Weird and who seemed to be working in unrelated areas.

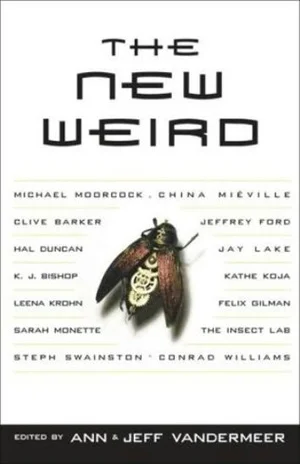

The obsessive confusion over who was and was not New Weird had resulted in a widespread failure to apprehend the importance of the New Weird moment. Taking its cue from early critics, the field has tended to regard the New Weird as little more than a failed attempt to launch a movement comparable to that of the New Wave, Cyberpunk or Feminist SF. Indeed, to this day the Encyclopedia of Science Fiction’s entry on the New Weird is little more than a few short paragraphs that pass vague comments about “ambience” before tentatively associating the movement with the early works of China Miéville and Jeff “I don't think New Weird encompasses what I want to write” VanderMeer as well as a much later anthology. In fact, it was not until said anthology made its appearance that the confusing buzzword began to transform into a useful piece of critical terminology.

2.2 An Anthology

Ann and Jeff VanderMeer’s 2007 anthology The New Weird is one of the most sophisticated themed anthologies ever produced in the fields of Science Fiction and Fantasy. Designed to retrospectively imbue the New Weird with the kind of internal ideological consistency that most of the self-identified New Weird authors were desperate to avoid, the book opens with an introduction that downplays the discussions that took place on the TTA Press forums. In place of M. John Harrison’s deliberate non-compliance we have a far more conventional and useful origin myth including links to the pulps, links to the artier aspects of Horror cinema, links to cool magazines, and links to a much broader critical category referred to as “The Weird” and fleshed out in a VanderMeer-edited companion anthology that would appear four years later. The introduction even goes so far as to provide a “working definition” of the New Weird sensibility:

New Weird is a type of urban, secondary-world fiction that subverts the romanticized ideas about place found in traditional fantasy, largely by choosing realistic, complex real-world models as the jumping off point for creation of settings that may combine elements of both science fiction and fantasy. New Weird has a visceral, in-the-moment quality that often uses elements of surreal or transgressive horror for its tone, style, and affects — in combination with the stimulus of influence from New Wave writers or their proxies (including such forbears as Mervyn Peake and the French/English Decadents). New Weird fictions are acutely aware of the modern world, even if in disguise, but not always overtly political. As part of this awareness of the modern world, New Weird relies for its visionary power on a “surrender to the weird” that isn’t, for example, hermetically sealed in a haunted house on the moors or in a cave in Antarctica. The “surrender” (or “belief”) of the writer can take many forms, some of them even involving the use of postmodern techniques that do not undermine the surface reality of the text.

Less a “working definition” than a sort of vague discussion, this account of the New Weird sensibility is not only at odds with the highly contextualised sensibility explored in the original discussions, it also bears only a passing resemblance to the ways in which the term was used in the immediate aftermath of those discussions. All reference to the British SF boom of the early 2000s is elided, as are references to the Science-Fictional aspects of the New Weird including the importance of M. John Harrison’s Light and the involvement of more typically SFnal writers such as Justina Robson, Al Reynolds and Paul McAuley.

Having reduced the New Weird/TTA Press moment to little more than a colourful anecdote, the VanderMeers set about re-inventing the New Weird as precisely the kind of easily-commercialised and intellectually sterile marketing opportunity that Jeff VanderMeer had initially worried about, and which many self-identified New Weird writers argued against. The short fiction section of the book provides the New Weird with what people like Kathryn Cramer were crying out for: A) a set of canonical texts, B) an identifiable group of members and C) a list of literary ancestors that provides the movement with both an ideological hinterland and a veneer of historical respectability. I mention Cramer in passing but the New Weird described in the VanderMeers’ anthology looks more like the round hole that Cramer was trying to sell than the square peg that Harrison, Miéville, Robson and Swainston were attempting to carve.

Thankfully, as emphatic as the anthology’s reinvention of the New Weird may be, its tone is far from absolutist. In fact, Jeff VanderMeer displays laudable self-awareness by admitting not only that his rejection of the New Weird “seems premature” but also that the book’s attempts to pin down the New Weird are really little more than the latest part of an on-going evolution and redeployment of the term:

The proof is that it has taken on an artistic and commercial life beyond that intended by those individuals who, in their inquisitiveness about a “moment,” unintentionally created a movement. It is still mutating forward through the work of a new generation of writers

The VanderMeers flesh out their commitment to an ever-evolving concept of the New Weird by including a selection of posts from the TTA Press discussions as well as a number of critical essays that show how the term has come to mean different things to different people. For example, Michael Cisco’s essay “I Think We’re the Scene” talks about the problems in defining the New Weird before concluding with a radical departure from anything that had up to that point been said about the New Weird:

The distinction between genre literature and general literature is bogus, at least in any non-colloquial sense of these terms. What is “general literature”? If we begin to define it, even assuming this definition can be uncontroversial, we are already outlining tendencies or rules which are indistinguishable in kind from those that are used to define genre literature. The distinction between genre and general is an evaluation from the outset, and not an innocent differentiation. The New Weird might be better defined as a refusal to accept this evaluation of imaginative literature, whatever form it may take. So it is not for reason of influence alone that such authors as Borges, Calvino, Angela Carter are invoked by many of those in the imaginative camp, but also because these authors are obviously both fantastic and literary. Each after their own fashion, as you would expect.

A lot of people would happily locate the work of Michael Cisco within the contested ground between genre and mainstream literature, but few (aside from Cisco himself) would extend that characterisation to the New Weird. Aside from the fact that many of the original New Weird authors seemed more worried about being subsumed within the mainstream than they were of being labelled ‘genre’, none of the VanderMeers’ adopted ancestors or fellow travellers associate the New Weird with mainstream literary culture.

Far more interesting is the collection of short essays provided by European writers, critics and editors who explain what the New Weird means to them in the context of their own local scenes. Aside from being gloriously at odds with each other, these essays suggest a desire to use the New Weird as a universal antidote to traditional publishing categories. The Czech editor Martin Sust describes how the term ‘New Weird’ has been applied to a publishing line that includes works that simply don’t fit within established SF, Fantasy and Horror publishing guidelines:

How do we pick books for our New Weird line? Every book must have something more than cross-genre leavings (science fiction, fantasy and horror). Every book must do more than attempt to create a story with the use of techniques more common to mainstream literature (like surreal visions for example). It must have a truly unique spirit and the desire to create something both good and new.

Sust’s essay is also an excellent example of the ways in which the rhetoric of evaporating genres can prove problematic: Whenever an author or a critic praises a story for its willingness to ‘challenge genre boundaries’, they are dignifying those expectations with a response and thereby suggesting that genre expectations are still a part of the cultural landscape. In other words, every time a writer or a critic decides to ride out against traditional genre boundaries, they are asserting that genre boundaries continue to exist and thereby (perversely) ensuring their continued existence.

This process of inadvertent reification is particularly obvious from the descriptions of the Czech genre scene contained within Sust’s essay. Faced with a rising tide of genre works that did not fit within their carefully curated marketing categories, Czech publishers appropriated the term ‘New Wave’ and used it to relieve the pressure on traditional genre categories and so ensure the continued existence of those traditional categories, at least in the short term.

The identification of the New Weird with both the dissolution of traditional genre boundaries and the importing of techniques from the literary mainstream are also central to Darja Malcom-Clarke’s essay “Chasing Phantoms” which concludes with the vital observation that the exact nature of the New Weird matters a lot less than the changes the term brought about:

That’s why, in once sense, it doesn’t matter if the New Weird “actually” exists — whether it’s just a rogue chill breeze raising goosebumps, or whether there really is a phantom rattling the windows and making discomfiting noises here. Because of the conversation surrounding its possible existence, the New Weird has changed the speculative fiction landscape, widened the horizons -- a lot or a little depending on where you’re standing. For this reason, I expect this particular phantom will continue to haunt the literary landscape for a long time to come.

Before the New Weird anthology, the New Weird was an ill-understood literary moment that seemed to have something to do with China Miéville. After the publication of the New Weird anthology, the movement became not only a good deal more concrete but also a potential market.

One of the more interesting pieces of post-anthology commentary on the New Weird comes in an interview with the commercial Fantasy author Mark Charan Newton who recalls that he:

wrote a novel in this world before THE REEF -- which got me my agent, John Jarrold, but it was in that curse-word category, the New Weird, which no publisher anywhere in the world wants to touch. The New Weird is dead. It was barely alive to begin with. So after this, I concerned myself with more traditional settings, and assiduously set about building something much bigger and more widescreen.

Newton’s puzzlement over the New Weird remained as the years saw him returning to what was now being referred to as a ‘sub-genre’ with varying degrees of hostility. However, after reading the VanderMeer anthology, Newton’s attitude towards the commercial viability of the New Weird seemed to change:

So what happened to the New Weird — or at the very least a conscious literary movement within the fantasy genre? Did readers not embrace it? Was it sucked into other sub-genres such as urban fantasy? I don’t buy the latter argument, because to me it was not merely a cheap aesthetic.

The last I heard of it was in Jeff’s anthology. I even feel vaguely nostalgic reading the product description: “a clear portrait of a multi-faceted and undefinable sub-genre and a statement that good literature has no boundaries.”

Perhaps I’m just a sucker for literary movements, because these things certainly keeps readers and writers on their toes. But anyway, if you see the New Weird, tell it I said hello.

The VanderMeers’ anthology may have shanghaied the New Weird and turned it into something a lot less interesting than it had once threatened to become but it also revived the term as a commercial and intellectual concern. After lying dormant for a number of years, the New Weird was suddenly alive… people were writing and thinking about it again.

2.3 A Marketing Gimmick

Newton was not the only person surprised by the New Weird’s sudden commercial viability. Paul Kincaid’s review of the VanderMeer anthology cuts straight through the critical cant and focuses on market conditions. Luke-warm on the fiction and noticeably impatient with the VanderMeers’ attempts to both emphatically define a sensibility and then distance themselves from the suggestion that this definition might be binding, Kincaid ends his review unconvinced that the New Weird was ever anything other than a marketing device used to draw new readers to the Fantasy genre by publicising some of its edgier and ambitious works:

The underlying message that comes across most clearly is a tiredness with the sorts of fantasy represented by sub-Tolkien clones and a desire to take back the genre, but that seems to amount to a reinventing of the literary fantastic from inside the genre rather than outside. And indeed while there is a rather over-enthusiastic love of gore and disgust, in reality little that is done here is not found elsewhere in the literary fantastic. But that is not what tends to be labelled as fantasy in the bookstores, so we come back to new weird as a marketing category.

This characterisation is echoed by Farah Mendlesohn and Edward James in their book A Short History of Fantasy:

New Weird: a marketing category (or perhaps a movement) around the turn of the millennium, which explored new and often disturbing ways of looking at fantasy motifs and at the borderlands between science fiction and fantasy.

Despite its many flaws, A Short History of Fantasy is the only study of the New Weird to address the clear cultural fault lines present in the original discussions. Quite possibly inspired by the unpopular distinction between British New Wave authors like Ballard or Moorcock and American New Wave authors like Zelazny or Disch, this unique approach is immediately undermined by the controversial decision to include a commercial Fantasy writer like Joe Abercrombie in the British New Weird and notable American short fiction paragons Ted Chiang and Kelly Link on the American side. Mendlesohn and James may well have hit upon an interesting trend in contemporary genre writing but the decision to identify that trend with the New Weird seems somewhat confused.

The post-anthology attempt to describe the New Weird as a marketing gimmick can be seen as a product of cognitive dissonance:

One the one hand, the New Weird simply did not fit with how most critics and industry professionals saw the history of the genre. Here was a movement born of confusion and perversity that never generated as much as a manifesto let alone a set of canonical works or authors. By the standards of Cyberpunk, Feminist SF, Radical Hard SF or even Mundane SF, the New Weird was both a catastrophic intellectual failure and a PR professional’s worst nightmare. How could you talk about, let alone market a movement that didn’t appear to stand for anything?

On the other hand, the VanderMeers had just published a slickly produced, well-received and highly visible anthology that proved that the New Weird could not only fuel interesting discussions but also sell books.

The New Weird sold like a movement and supported critical discussion like a movement and yet it lacked the ideological texture that the history of genre writing has taught us to expect from a movement. Cramer got out of this intellectual impasse by suggesting that the New Weird was first a sub-genre and then a mode. Late-2000s critics resolved their cognitive dissonance by referring to the New Weird as a marketing scheme. Mark Charan Newton’s volte-face over the commercial viability of the New Weird found its mirror image in a post by a then-blogger, now-publisher named James Long who concluded that:

The problem with the New Weird is that it doesn't have a marketable identity - it's so hard to define, so abstract, that it effectively renders itself uncommercial. While this is attractive from an artistic perspective, it basically meant that publishers didn't know how to handle it and subsequently (and understandably) were reluctant to invest in it - one reason why the genre rapidly declined.

The attempt to determine whether the New Weird was still a going concern even made it as far as academia where Alice Davies produced an essay for the Winter 2010 edition of the SFRA Review in which she summarised the major beats of the TTA Press discussions and concluded: